Dear Diary…not a lot happened, actually

On Friday night, admittedly a few cocktails down, I clambered (gracelessly, with much grumbling) into our dusty overstuffed attic on a quest to find an old photograph I could picture in my head and that I just knew I must have kept.

I didn’t find it. What I did unearth, however, was a small hardback diary for the year 1999–2000. I had no memory whatsoever of owning this notebook. I was therefore fairly sure I couldn’t have written in it. Surely I’d remember the book itself, if I’d ever written on its pages?

But no. My memory had just glossed over it, apparently. In the last few months of 1999 I’d kept careful notes of my student loan budget and outgoings, and also added short personal entries occasionally. Side note: I had £18 spare per week. How did I survive?!

The diary entries continued past Christmas and into the start of the new millennium (the passing of which I didn’t bother commenting on, although I can clearly remember my two-tone purple shirt I wore on that illustrious night when the Millennium Bug failed to be a thing).

As I read the entries, as self-indulgent and teenagey as they are, I remembered more and more about writing them. I remembered sitting in the little room where I did my university homework, with its offensively 1990s lilac walls (I’d painted them myself, badly) and the blow-up armchair I got from one of the stands at Fresher’s Week.

I remembered, too, the various events I had written about: a nervewracking NCT playdate to which I took my one-year-old daughter, in which she climbed into a coal scuttle and spread black soot over the host’s pristine cream carpet; a rare impromptu visit to a university nightclub with my best school friend and her ebullient American boyfriend; an assignment on Contract Law for which I got 79%. (This was an excellent grade for me, and worthy of note in a way that the Millennium obviously wasn’t).

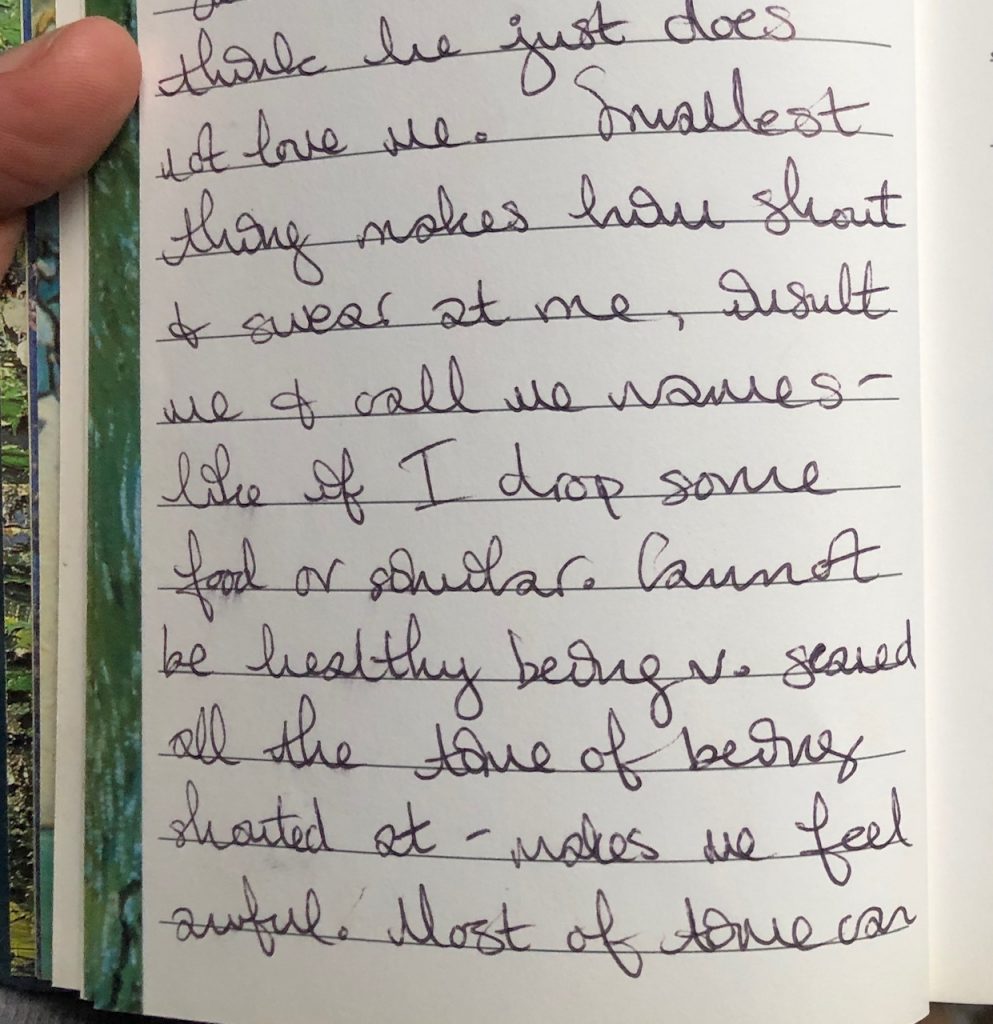

I also remembered, with a cold wrench, the bone-deep despair which had driven me to write about my baby’s father on 8th February 2000: “Want to be happy together for daughter’s sake but think he just does not love me. Smallest thing makes him shout and swear at me…call me names…cannot be healthy”.

Reading my own strangely familiar and yet entirely unfamiliar words, I fiercely wished that I had written loads and loads more of them. At the time they’d felt pointless, a self-indulgent and prosaic record of a life that I did not think was really worth recording, and I felt a bit daft doing it. Over twenty years later, though, they’re precious even though they’re so banal. They’re the seeds my current life grew from. If I had more of them, I feel like I’d understand myself so much better.

As I read them I was reminded again, too, of something that my dad said to me last year, after his partner suddenly and tragically died in the April of that year. He told me that he derived huge comfort from her diaries, which she had faithfully kept for years.

Her short, factual but — crucially — regular entries had spanned all of their long life together, making notes of dates and places and people, and reading about it now makes their joint past more real for him. He still reads back through the notebooks regularly, padding out her sketchy notes with his own memories. They’ve become his most treasured possessions.

A diary becomes, so quickly, an historical record, valuable not just for its insight into the mind of its author but for the incidental mentions of all the tiny insignificant details of a life. These are the things that make history matter.

When I recently read “A Notable Woman: the Romantic Journals of Jean Lucey Pratt” (took me forever, it’s the size of a breezeblock), I was fascinated not just by her obsessions and crushes and unconventional career path – but by the throwaway comments she made about blackening the hearth, darning stockings, making jam and chutney, and buying plucked ducks from door-to-door salesmen. Pratt lived through the Second World War and the creation of the NHS; but these huge, seismic changes to the fabric of the UK played second fiddle to her romantic escapades and her interior monologues. As they would for most of us. (As they did for me, when I didn’t bother mentioning the millennium but talked about a babygro I’d bought my daughter). And Pratt’s book is gripping because of this, not despite it.

Since my dad told me about the value his partner’s diaries have for him, I’ve started one again. For the first time in about a decade, I am making a short note of each day’s events. I’ve chosen deliberately a paper diary with only short spaces available, so as not to feel daunted, and I’m making sure to put brief fact-based notes in it, almost like a checklist. Basically, I’ve taken away the pressure I always used to put on myself to be eloquent or to try to explore my feelings. No one’s up for a deep-dive into their emotional crevasses at bedtime, let’s face it.

So I’ve stripped my record to the bare bones, and it’s as dry as dust to read. The thing is, though, I’ve realised that doesn’t matter. I can flesh the bones out later if I need to; the words are a prompt to my memory, not a replacement.

Already, I can flip back 6 months and be surprised by the patterns I observe in the things I did and the people I saw. For example, my notes about the routine of my life before Covid-19 restrictions kicked in now feel like a sort of fiction. Were dance floors ever a thing, really? At the moment they feel illusory, but then I read a note about going dancing with friends in February and remember everything about their sticky, ear-shattering joy.

Basically, I’ve changed my mind about a diary’s purpose, and about it’s value. I think that often it can feel that there is nothing of value to say, or that we have to think of something specific to say before we put pen to paper. I definitely used to think that. Now, though, I think the whole concept of a diary should be its proof that pens should hit paper before there’s anything to say. That the act of note-taking makes the notes worth it, even if that takes years.